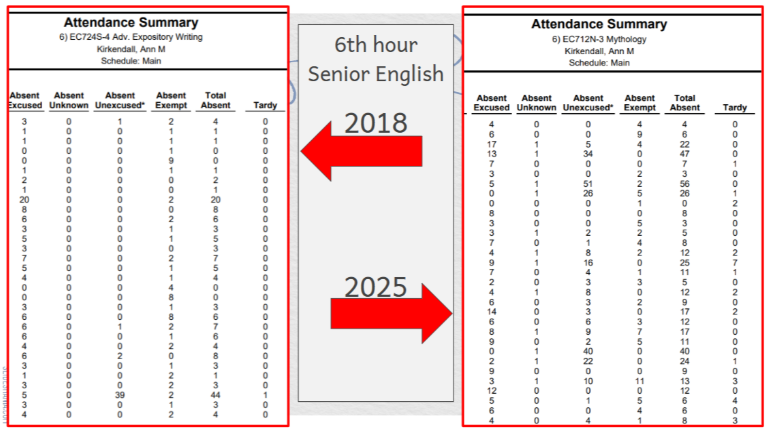

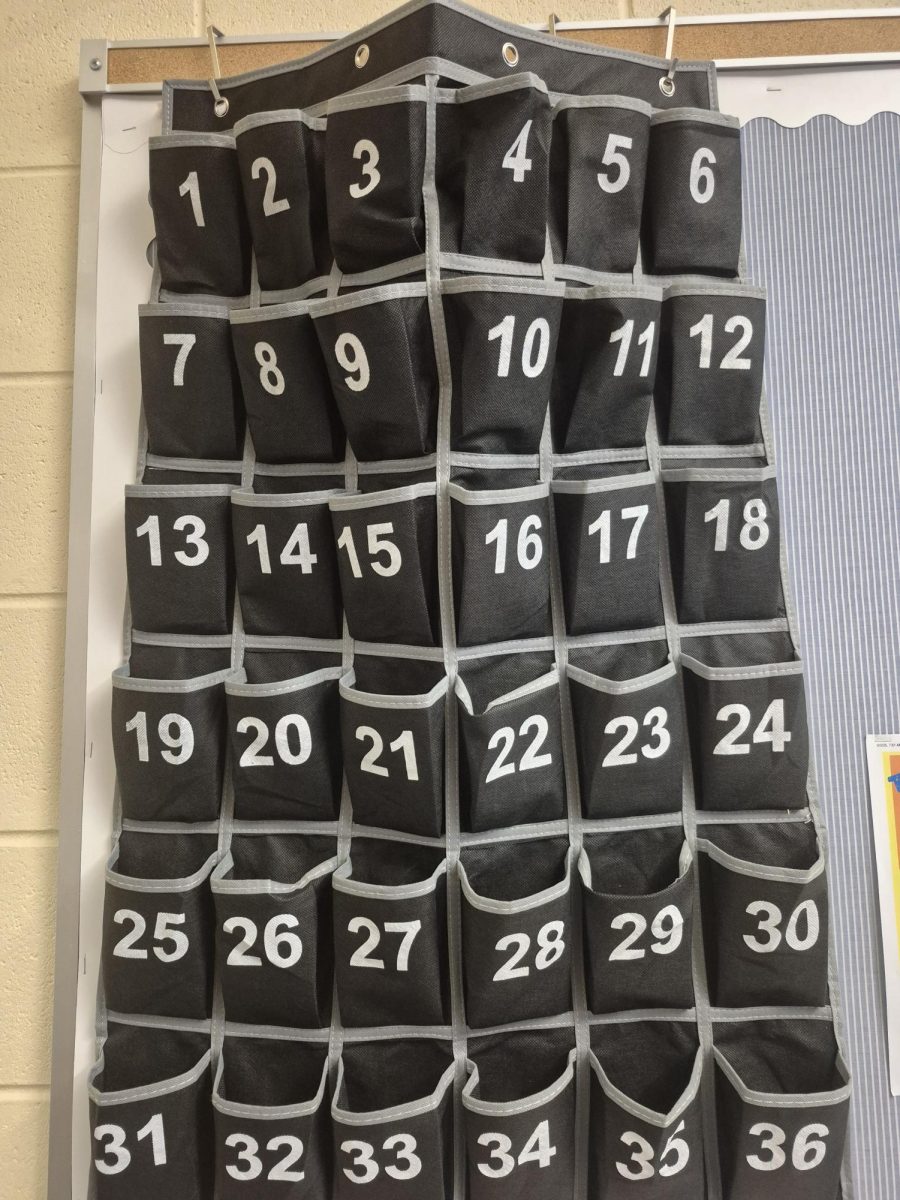

A teacher records that three of her students are missing, a full fourteen percent of the class. This is typical; how is she expected to start a new lesson everyday when she has to constantly review to catch the rotating cast of missing students up on information.

When excused and unexcused absences add up to any one student missing ten percent of school days for a given period, that student is chronically absent. According to the US Department of Education, this describes the state of attendance for over one fifth, or twenty percent, of high school students in the US.

The Department of Education estimates that this 1:5 ratio of chronically absent students is roughly descriptive of the West Ottawa Public School District. This is comparable to the national average, though still worrying given that the twenty percent national ratio refers just to high schoolers (who generally fare worse in their attendance when compared to younger students) and our twenty percent ratio includes younger students as well.

Chronic absenteeism is a problem that affects minority students disproportionately as well, with Hispanic and black students seeing higher rates of chronic absenteeism than the overall average. The Public School Review reports that the West Ottawa Public School district is composed of more minority, and especially hispanic students, than average, potentially explaining why our district sees such high rates of absenteeism.

This problem has negative effects according to the University of Delaware, and is the single biggest predictor of school dropout, negatively affecting both the academic performance of the chronically absent student and also the performance of their peers. Chronic absenteeism also increases negative life outcomes, such as criminality and poverty.

Other sources agree on the problematic nature of this issue. For 86% of suspended students during a Johns Hopkins University study, chronic absenteeism served as the very first warning sign of future behavioral issues, so reducing the former may be the first step in tackling the latter. Their study indicates that reducing chronic absenteeism can have positive impacts, with students who exit a state of chronic absenteeism seeing significant improvements in reading and math, as well as reaching school enrollment rates on par with those who’ve never been chronically absent.

Chronic absence is a dynamic issue and has no one identifiable source. The advocacy group Attendance Works identifies familial and home environments, inadequate transportation, resource insecurity, behavioral issues, a lack of engagement or support, and a conflicting work-high school relationship as primary motivators for absenteeism. The Department of Education blames inconsistent attendance on factors such as “poverty, health challenges, community violence, and difficult family circumstances.” Like Johns Hopkins University, the University of Delaware sees the value in community organizations and teachers intervening to aid students who suffer from poor situations.

According to Lisa Kephart, an attendance secretary for West Ottawa, chronic absenteeism got worse after the Covid-19 pandemic, with her saying that there was “a shift.. In the value that they (students and parents) put into attendance.” When the official school policy was for students to miss two weeks at a time, like it was during covid, staying home for other reasons felt more justifiable. This is compounded by the increasing focus people have given to mental health in recent years, according to Kephart. She emphasized its importance, but cautioned against getting out of the habit of going to school.

Of course, certain factors, such as mental health and family environment, are well beyond the scope of a high school administration. With that being said, there are absolutely ways schools can successfully address this issue. The Education Resource Information Center encourages schools and governments to actively connect with families about attendance, celebrating attendance milestones and finding mentors for students. The school management organization School Mint also highlights the importance of tackling tardiness before it gets out of hand and becomes chronic absence, providing positive reinforcement for improved attendance.

The Johns Hopkins also indicated that the most promising impacts could be had in impoverished and minority communities. Their study concluded that the most impactful interventions involved tracking individual students and implementing mentorship programs. These mentors included teachers and school administrators, community leaders and nonprofit groups, and in-school peers. These mentors and teachers would help students integrate back into the school environment as well as motivating them to not miss school in the first place.

The Johns Hopkins study also pushed the importance of recognizing and celebrating improvements in attendance and being vigilant about lapses. Attendance records were made easily accessible to parents with online resources, something already done at West Ottawa. Mentors and staff also met regularly to discuss the success of their efforts overtime and identify weaknesses.

The University of Delaware study warns against over reliance on punitive measures in dealing with the problem, instead emphasizing the importance of school-family communications and attendance tracking: “An experiment that sent automated text messages to parents and guardians about their student’s absences, low grades, and missed assignments, was found to reduce course failures by 38% and increases class attendance by 17%.”

Now that curtailing chronic absence has been demonstrated to be both desirable and possible, it makes sense to turn and focus on the ways that West Ottawa High School has responded to it. Kephart characterizes our response as dynamic, saying that school staff will “keep trying things to figure out… what’s the most effective.” The school must strike a balance, we might try to “dangle more carrots and to use more sticks,” says Kephart.

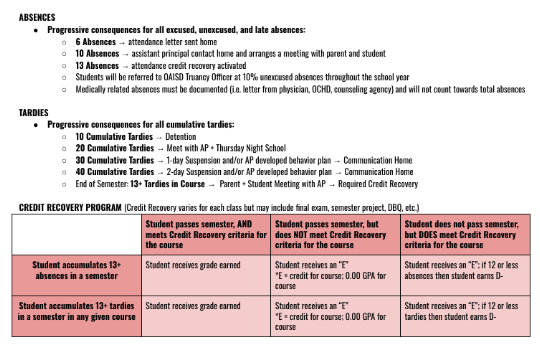

The major policy choices made by our school were the school dance rule that prevents students who miss 10% of school days from going to dances and the attendance and tardy policy that progressively penalizes attendance issues as they get worse. This addresses tardies before they have the chance to turn into absences. Additionally, the administration is in the development stages of a targeted tutoring program which, in the words of Kephart, “replaces… some of that (Thursday night school) with actual tutoring instruction.” Something like this certainly seems a step in the right direction, students no longer have to feel overwhelmed or like catching up is an insurmountable task because they are given personalized lessons.

Trends in terms of school attendance are concerning, both locally and nationally. More and more students are being actively put at a disadvantage because of a practice that seems to be viewed as more and more acceptable. Even with this, there should be optimism, though, and chronic absenteeism is a problem that has tangible solutions, specifically mentoring and tutoring programs, active school-home communications, and a strong sense of community seem like they are well worth the effort that they require. Attendance at West Ottawa is worrying, but it seems like the school is taking an active approach to get heads back in the classroom.