The one that got away

October 1, 2021

I do not remember the first time we met. I have always seen her as the daughter of my mother’s friend, and eventually as my close friend. I do no t remember, as well, when I learned that she was adopted.

t remember, as well, when I learned that she was adopted.

She was who she was and I did not truly care about her past before arriving in Italy.

She was the one always late, the one who could stay hours in a shop and come out with a t-shirt that she doesn’t even like. She was the one who, when I brought her for the first time on my motorcycle, screamed the whole time begging me to slow down then she happily told me that she enjoyed it. She was the one always laughing at every joke, even hours afterwards. Sometimes, though, she just suddenly stopped laughing.

After years of friendship, though, where we never talked about it; my curiosity started to become bigger, and bigger, and bigger inside of me.

Then, she decided to tell me the truth.

We’re far, so far from each other now, thousands of kilometers and an ocean away; she’s in Italy and I’m here in America.

When I had to leave for my exchange year she told me: “I hate saying goodbye to people. I’m scared of abandonment.”

With a series of long phone calls, we decided to break through the last barrier in our friendship. Now, we’re closer than ever.

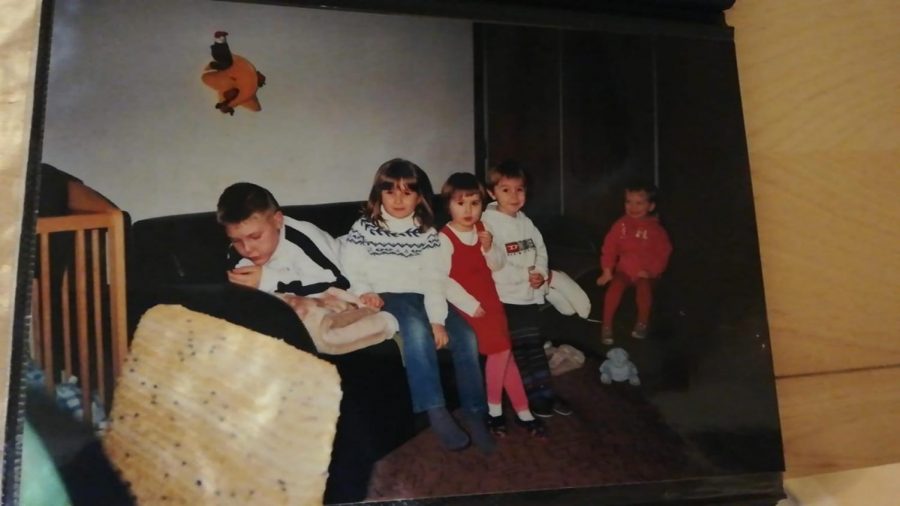

“I was 8 years old when Mariella and Franco (her parents) adopted me. My sister was 6. This is the reason why I remember everything about what happened before, and she doesn’t.”

She pauses on the other end of the phone. “My sister, my sister had an important role in my life. For her, I had to grow up fast. Faster than a kid in an orphanage usually does. I had to be her mum. I was acting like a mum: I took care of her for everything. And I kept doing it also when we had our family in Italy. I do not regret doing it. I like seeing her growing up well and knowing that, in a small part, it’s also thanks to me.

My father still jokes about it, telling me to stop acting like a mother.

After all, it’s not necessary anymore.”

“It doesn’t hurt me to talk about it. I’ve always answered questions when people asked me,” and I started feeling guilty. Maybe I had to ask her earlier about her life before arriving in Italy? Or was she lying? Even if she was, I had already started the conversation. So I started asking, asking everything I always wanted to ask her in years.

I wanted to know more about her sister. I have a younger sister. I think about her without me in Italy and a piece of my heart dies. How could she manage the fear of being divided from her? Forever? Only an older sibling can understand that feeling. That deep dread.

So I asked. “Were you scared of being adopted into two different families?”

“I prayed every night. I was asking to have a family, to know what it felt like. For me, and Giovanna’s sake. I promised I would always take care of her.”

“We’ve been in different places. In the first one, we were separated. In the second one, we were reunited. In the third too. Sentivo che non ci avrebbero piú divise. I felt they could not separate us anymore. And then I always said it, it was my only request: either me and Giovanna, my little sister, together, or I didn’t want that family; she had to be forever next to me. Even though having a family as soon as possible was my biggest desire.”

And I could not understand. Understand that desire. Because I was born in a family, I could not fully understand. I asked more then.

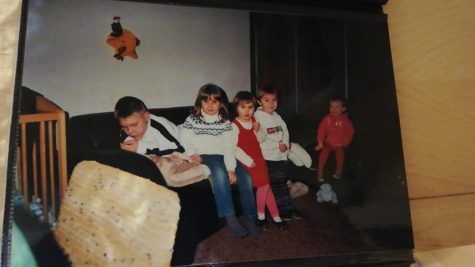

“It’s not like they didn’t love us. They did. In the third place we’ve been, it was the house of this lovely woman: she used to take some kids from the orphanage and keep them with her, together with her natural children. There were four beds and the beds of her kids. So it’s not like they didn’t love us. We were just so many. So many kids.

With our family instead, all the attention was on us, just for us, about us. Volevano bene solo a noi. They just loved us.”

I could not know how she felt and how she was feeling while she was opening up, but I’m sure about how I was feeling: I had chills and I could not think of anything other than why, why people have to suffer so much. Why are innocent people always the ones who suffer the most?

“What were you excited about when you had this big change in your life?” I wondered, ignoring my feelings and the strong desire to start crying.

“I just wanted to know what it was like to have parents.” and I felt even worse.

“Anyway, it’s not like I had time to realize what was going on. One morning like the others, they woke me up and they dressed me up (in a hideous way, by the way), they brought me to the court and then to a place where I had to be with my parents for two months, to get to know each other. But do you remember the woman I told you about? One day I ran away to say goodbye to her. For this reason, they moved us to another place, two hours away, to not influence my choice. But I couldn’t even say goodbye to anyone. I still remember all my friends there.”

I can not imagine how important they were for her, such a help in that challenging time. But she didn’t even have the chance to say goodbye to them forever.

“Were you somehow feeling bad about having a family, when they still had to stay there?”

I heard her stop breathing for a moment on the phone. Then she kept talking.

“No. At that moment I was selfish. Ero troppo occupata ad essere felice, I was too busy feeling happy, non ho pensato a nessuno, I didn’t think about anyone.”

Memories are what make us understand what we need, where we have to go, who we are. How could I not ask for memories? Not about the ones we shared, but about the ones she only could know about.

“I remember the school clearly. I remember the classes we had, I remember that class we had in the afternoon, the binder we used as a book, that I was next to the window…”

“The school’s food? Disgustoso. Awful.”

Believe me, if I say that I felt the taste of that horrible food in my mouth, just listening to how much disgust she put in her words.

“The meat was nasty, it tasted like jelly. That’s the reason I can’t stand meat now.”

“To go from the house of the ciocia (aunt, in Polish) to school we had to walk through a market.

With her, we lived a normal life. Her husband was a policeman, he had a German shepherd.”

I was wondering if that had to do with her passion for dogs now, but she gave me no time to ask because she kept talking.

I heard her voice changing considerably. It was like she was trying to throw out through her mouth something too big to put into words. “That night seems like yesterday.”

So I understood what I was about to listen to. And I fell silent.

“I was on the couch with my birth mother and my sister, I don’t know where my father was. Suddenly we heard someone knocking harshly on the door (we lived in an apartment), my mother stood up and opened the door, and around ten police officers appeared who started making a mess.

A woman came next to me and told me to follow her but I didn’t want to, so I started trying to escape. But she took my sister and brought her outside the house.

Meanwhile, my father appeared and started screaming, the police officers started checking everywhere in the house.

After moving the couch, they stared at my parents. I went there to check: there were many bottles and packed envelopes, maybe drugs.

After that, I saw everything in slow motion, I just remember seeing them taking my mother and my father, trying to free himself, the policemen handcuffing him, slamming him against the wall.

I woke up in a car, with my sister sleeping on my knees.

I don’t know how old I was when I was removed from my house.

Sometimes I still dream about this event.”

If I was not here, on the other side of the world, I would have loved looking her straight in the eyes. I tried to figure out her face in my mind, with her so-not Italian features, which betray her every time she meets someone, so they start making their bugging questions; her blonde hair, her dark eyes. I felt like I was talking to someone else like she wasn’t one of my oldest friends. I felt like she was a stranger at that moment. Because I never fully knew her. I guess I will never know.

“Making my story be read in America it’s weird, but I’m not unique. There are a lot of people like me. I’ve never been ashamed of being adopted because I feel extremely lucky to have met parents like Mariella and Franco. They gave me a life, thousands of opportunities, they made me travel the world, they allowed me to realize one of my dreams, horse riding, and I could participate in the Italian international game. I could meet amazing people, I could go to university. Thanks to them I have a house, people who love me.

I’m never going to stop thanking them, as well because a grazie, a thank you, would never be enough for what they gifted me.”

Adopting is not an easy process, both in my country and here in America. But listening to the stories of my friend and American people who adopted their children, now I’m even more sure of one thing: what matters is not the blood or the skin, but, as Agnese said, it’s essere amati, being loved.

Sempre e per sempre. Always and forever.

Federica • Nov 23, 2021 at 9:22 am

i’m crying. what a story. it’s weird to think it looks like a movie, but that actually these things are very common.♥️